Welcome, to the story of an ordinary citizen trying to grasp an extraordinary situation.

Quite some time ago the author came to realize his many limitations, and not too long after that he came to a sort of peace with this knowledge. However, not quite so long ago he also realized he wasn’t going to be able to just shut up about matters clearly above his pay grade.

Being an occasionally considerate soul, he realized friends and family might not be, well, quite as interested in these issues as he was.

Welcome, then, to an old school web site, where this average citizen explores topics he thinks are important. Whether you find any of them interesting or important is, well, for you to decide, of course.

A Threat Perspective

The unifying theme running through topics here is the concept of existential threats. Perhaps it is rooted in an early childhood fascination with dinosaurs, or perhaps it was a college interest in the collapse of the Roman Empire. Whatever its origins, it is now something I research in my spare time, and is the basis for the content of this site.

Clearly there are a great many threats out there, some near, some far. From my perspective, however, it doesn’t get much more existential, nor more threatening, than climate disruption.

Now mind you, in considering the information available, it is clear there exists a powerful set of narratives which either dismisses it as an issue at all, or considers it to possess, at best, a tremendous level of uncertainty.

While at some point I hope to be able to explore some of those narratives, at this stage it appears to me to be about as potentially catastrophic as can possibly be imagined.

A Climate Perspective

Given the fact I consider the issue to potentially be an extinction level event, I thought I’d lay out my take on things, and why I think most current approaches to dealing with the issue may not work out so well.

A Question of Scale

This is the issue that seems the most fundamental. Are those who do agree this could be extremely difficult thinking at the appropriate scale? I mean, the basic idea seems pretty straightforward. I think.

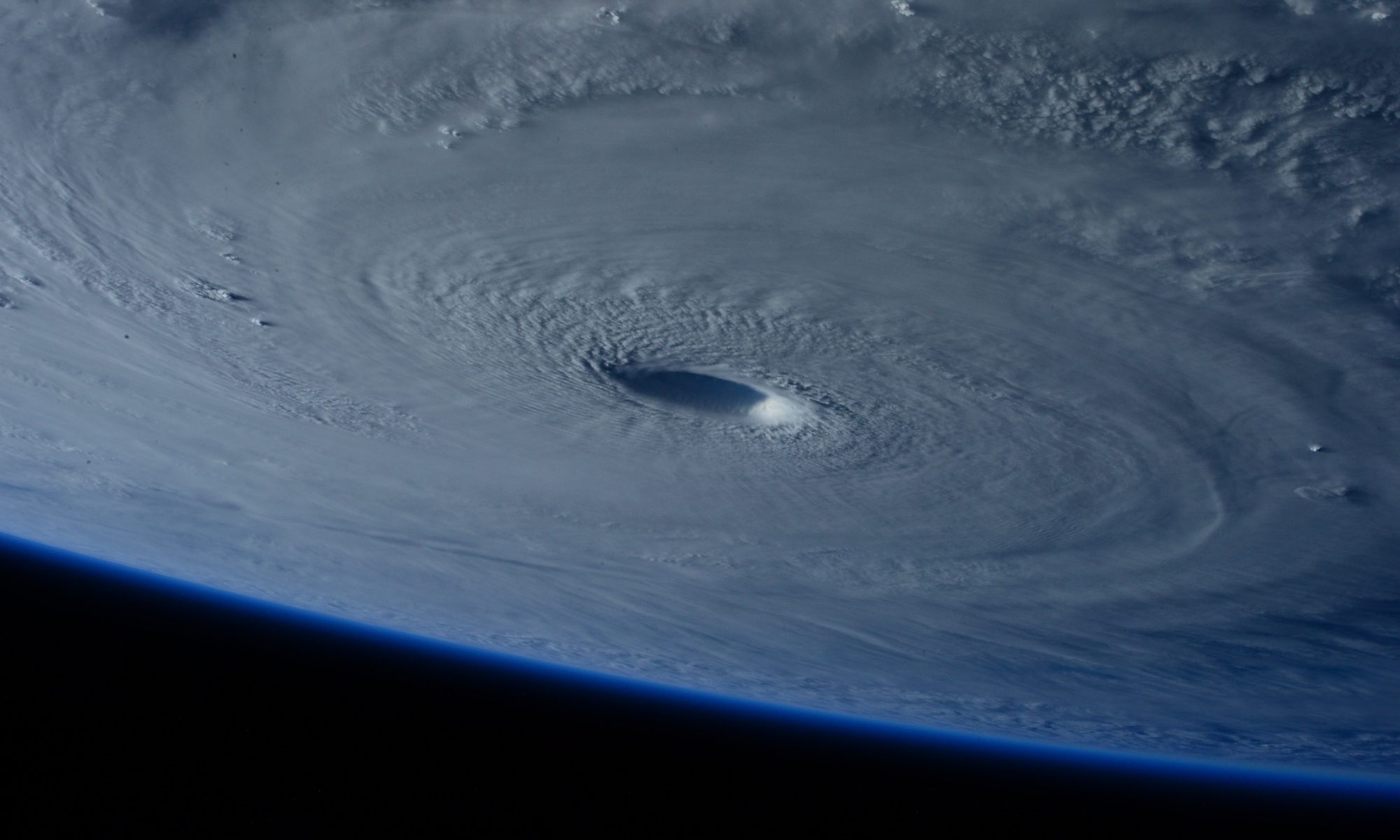

At just over 420 parts per million CO2 the Earth has seen a temperature increase of a little over 1 degree Centigrade above pre-industrial levels. We emit carbon and the planet slowly warms. One degree doesn’t seem like much, but it appears to be enough to begin melting the polar ice caps:

So at just a bit over one degree warmer we’re melting absolutely massive amounts of ice.

I can’t be the only one who thinks this indicates it is already too warm, and that we need to, well, go backwards. To cool the planet, at least to some degree.

While there are a number of suggestions out there on artificially cooling the Earth, if excess CO2 in the atmosphere is the underlying problem, it seems to me we’re not really dealing with the issue until we withdraw CO2 from the atmosphere and, well, put it some place.

So what sort of numbers are we talking about?

Bill McKibben, the popular green activist, has proposed 350 parts per million as a goal. I think 320 would be better, but let’s for a moment consider 350.

The last time we were at 350 parts per million CO2 it was right around 1990:

Or, in other words, to get to 350 we would have to pull down and sequester everything we’ve emitted for just shy of the past 30 years.

That’s an awful lot of carbon. So I guess I don’t understand the idea that it will be sufficient to gradually transition to renewable energy over the course of the next several decades. As the Keeling Curve continues to rise, so will the temperature, and with an absolutely minimal increase thus far we’re melting some rather, er, significant ice sheets.

However, for the sake of discussion, let’s assume the gradual transition to renewable energy is successful, and that in addition we are somehow able to find ways to mitigate the effects of any additional temperature rise.

Perhaps we are able to follow the path laid out by Mark Jacobson, a professor of civil engineering at Stanford University, and a frequently quoted source among green advocates, who thinks we can transition to an all renewable grid, if not by 2030, then at the latest by 2050.

As a result, let’s further assume we hit net zero emissions by 2050. Since the existing CO2 will continue to trap heat, even at a net zero emission rate, it seems reasonable to ask how long will it take for the CO2 to work its way out by natural methods, resulting in a noticeable decrease in average temperature?

Well, barring any sort of intervention, it appears it will come back down in stages. Much of it will come down in the course of decades, some of it in centuries, and a small but important amount will remain for thousands of years:

And in the short term, where will it go?

It looks like it will mostly wind up in the oceans. Additional carbon in the ocean, by nearly all accounts, will increase its acidity. It’s already increased it by a small amount, but that small amount is beginning to affect the formation of calcium shells used by all sorts of sea critters, many of whom form key parts of the ocean food chain.

In summary, then, if we do manage to transition to an all renewable energy system, with zero net emissions by 2050, we will nonetheless continue to experience unrelenting heat, acidifying oceans, and will continue to wreck havoc on the planet and the global food chain we depend on.

Given all this it seems reasonable to me to conclude we need to go carbon negative in the near term, do it on an epic scale, and sequester the carbon somewhere reasonably safe. No?

Which, if correct, seems like a pretty tall order.

Ideas, Anyone?

This is where things get sticky, of course.

Given what appear to be some basic realities, I think it might make sense to assume that whatever we do it

- Must operate at the appropriate scale

- Not be too disruptive

- Have measurable results

- Have some source of funding

Given the fact the results ought to be measurable, it is further worth noting

- Each part per million of CO2 is equivalent to a bit less than eight billion tons

- So, if we’re aiming to remove fifty parts per million, we need to sequester roughly four hundred billion tons

It’s pretty simple math, but clearly its anything but a simple proposition. In fact it isn’t surprising that a fair number of folks have concluded it is already game over, and realistically perhaps it is.

However, on the assumption we decided we were going to try to do something about it, what sort of approaches might we take?

If you’ve made it this far, perhaps you may like to take a look at an Approach.